5. Voiceover

The previous chapter dealt with a voiceover technique that helps the audience interpret pre-recorded spoken text as the inner thoughts of a body on stage, by linking those audio cues with live sung phrases. However, in Scene 14, Kane writes about the main character in the third person, indicating a third-party voice belonging to someone other than the main character. Here, a voiceover was used that was not linked to singing, that was not to be heard as belonging to a body on stage, that is not an inner monologue. In other scenes, I used this ‘de-personified’ voiceover for dramaturgical reasons, such as to represent the voice of an imaginary lover in Scene 11, or for musical reasons, such as so that the recorded voice could be truly screamed (which a singer cannot do on stage) in Scene 16. These scenes will be discussed here in order: Scene 14, Scene 11, Scene 16.

5.1. Scene 14

Lofepramine, 70mg, increased to 140mg, then 210mg. Weight gain 12kgs. Short term memory loss. No other reaction.

Argument with junior doctor whom she accused of treachery after which she shaved her head and cut her arms with a razor blade.

Patient discharged into the care of the community on arrival of acutely psychotic patient in emergency clinic in greater need of a hospital bed.

Citalopram, 20mg. Morning tremors. No other reaction.

Lofepramine and Citalopram discontinued after patient got pissed off with side affects [sic] and lack of obvious improvement. Discontinuation symptoms: Dizziness and confusion. Patient kept falling over, fainting and walking out in front of cars. Delusional ideas – believes consultant is the antichrist.

This excerpt of text from Scene 14 (Kane, 2000: 22) is in the style of medical notes about the main character. The scene documents ten different drug treatments for depression and the patient’s medical response to each, ending with a description of an unsuccessful suicide attempt by overdose. The text refers to the patient in the third person, and also to other patients and medical professionals in the third person. Therefore the speaker is neither the patient nor the Doctor/Therapist who is featured in the dialogue scenes. It is the voice of a third-party observer – presumably also a medical professional.

Any voiceover applied to this scene needed to be distinct from the ‘opera thought-bubble’ technique described earlier. The audience must not interpret the voiceover text as belonging to a body on stage, but rather that the voice comes from outside the stage, from a body that we cannot see, and therefore removed from the action that is happening on stage.

I considered three different approaches to dealing with this third-person text:

- The text is projected only. It is de-personified because there is no human voice element.

- The text is pre-recorded by a voice which evidently does not belong to any body on stage. For example, a male voice.

- The text is pre-recorded by a voice belonging to a cast member, although there is no sung (live) voice to which the pre-recorded voiceover can be associated.

I will outline how the scene was written first using approach one, but that developments during the rehearsal process led us to try approaches two and three.

Background research for this opera found examples of all of these approaches in theatre productions that also have an indirect relationship between character, narrative and performer, similar to 4.48 Psychosis. For example, in Hyperion. Briefe eines Terroristen, director/designer Romeo Castellucci projects statistics of the atomic composition of water in large typeface on a downstage scrim, synchronised with electronic beeps, forming a 3-minute interlude in the piece. Similarly, director Katie Mitchell and writer Alice Birch, in their piece Ophelias Zimmer (2015), project text descriptions of the five stages of death-by-drowning onto the set in interludes between stage action. The latter example is accompanied by a pre-recorded male voiceover and synchronised with music, while no bodies are visible on stage. Both of these examples use these interludes as blackouts, opportunities for scenic changes.

Inspired by these examples, I conceived Scene 14 as an interlude in blackout, to allow a scenic change, in line with Scenes 4, 8 and 20. Like those scenes, Scene 14 has a close synchronisation between music and projection, with the conductor on a click track and the projection exported as a video and synchronised to the click track. No voiceover or singing, either live or pre-recorded, was instructed; this was simply music and text, to be projected in large typeface, downstage, possibly on a scrim, similar to Castellucci’s piece.

To achieve this, Kane’s text was broken into the following fragments, using her punctuation and short turns of phrase as a guide. The absence of projected text (a blank screen) was instructed with [blank] and occasional punctuation was also synchronised with music (usually a staccato splash cymbal):

– Lofepramine,

– 70mg,

– increased to 140mg,

– then 210mg.

– Weight gain 12kgs.

– Short term memory loss.

– No other reaction.

– [blank]

– Argument with junior doctor whom she accused of treachery

– after which she shaved her head and cut her arms with a razor blade.

– [blank]

– Patient discharged into the care of the community on arrival of acutely psychotic patient in emergency clinic in greater need of a hospital bed.

– [blank]

– Citalopram,

– 20mg

– .

– Morning tremors.

– No other reaction.

– [blank]

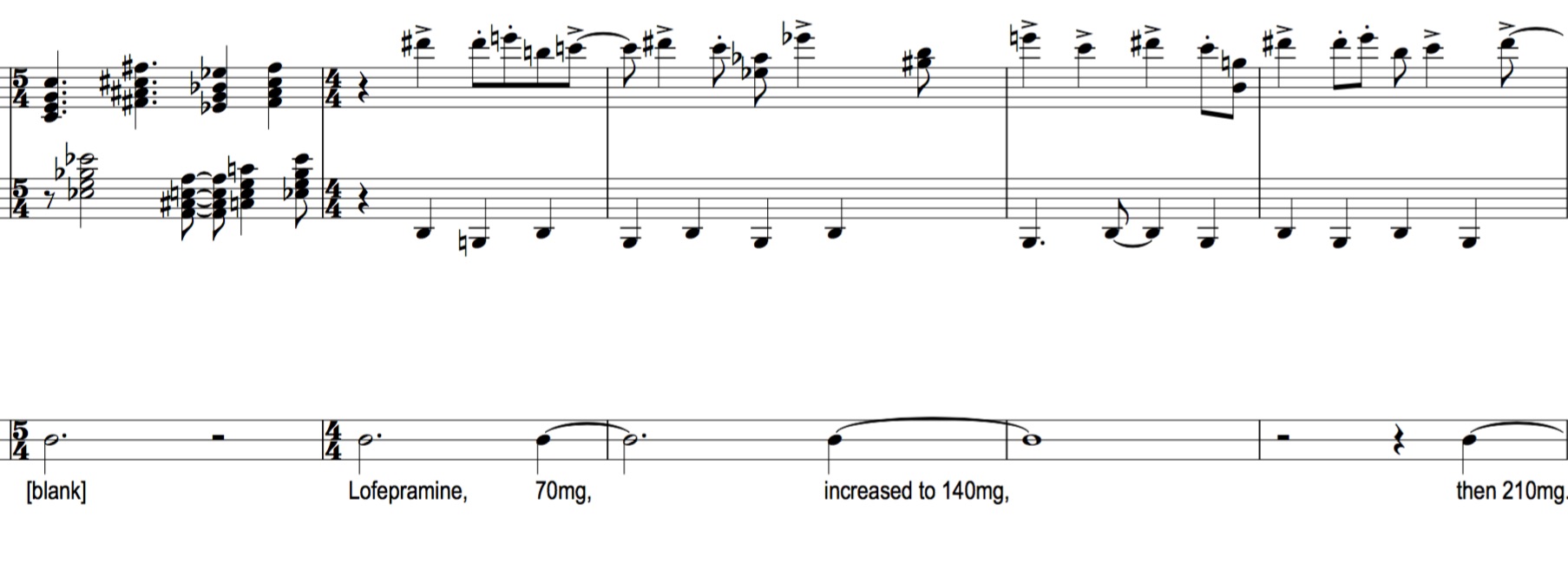

The synchronised projection was indicated in the score simply with the position of the each new projection slide; rests are simply for ease of reading, they do not imply a blank screen. Figure 17 shows the projection cue line in an excerpt from the score. The three-line projection stave indicates three different projection positions on the stage: stage left and right positions described in Chapter 8 – Percussion Dialogues, and the central position on the central stave line.

Figure 17: An excerpt of the score for Scene 14, showing the projection cue line, indicating the timing of each projected text fragment.

The excerpt of text above also illustrates Kane’s wry, dark humour, evident in this scene and in the scenes discussed in Chapter 8. This humour tends always to be associated with Kane’s descriptions of the medical profession, the NHS, treatment, the clinical-mechanistic approach to depression. Perhaps this wry sarcasm indicates a cynicism at the medical profession and their approach to treatment for depression. In Scene 14 this humour is best illustrated by the closing paragraph (Kane, 2000: 23):

100 aspirin and one bottle of Bulgarian Cabernet Sauvignon, 1986. Patient woke in a pool of vomit and said ‘Sleep with a dog and rise full of fleas.’ Severe stomach pain. No other reaction.

This pantomime of medical treatments deserved a comic musical setting. Musical material was borrowed from the ‘numbers scenes’, 4 and 20, which also functioned as blackout interludes and featured large downstage projection (see the example of Kane’s text for Scene 4 in Figure 6, Chapter 2). This music features three baritone saxophones supported by bass, piano left hand and accordion in unison syncopated basslines, against an angular syncopated melody in upper strings, piccolo, piano right hand and accordion. Since the piano and accordion carry both lines, the piano part in Figure 18 provides a good example.

Figure 18: A excerpt of the piano part from the score for Scene 14, showing the two-part counterpoint employed for most of the scene and the projection cues to which it is aligned.

This musical material is employed for most of the scene. However, specific situations described in the text are treated with comic word painting; here are some examples:

- Three references to weight gain or loss are accompanied by rising or falling string, accordion and piano glissandi with a slide whistle. See Scene 14, bars 17–18, 60–61, 120–121.

- Two references to sleeping are accompanied by a very high and quiet held chord in accordion and string harmonics, with a toy piano playing the tune of ‘rockabye baby’ in a slower metre. See Scene 14, bars 29–31, 137–143.

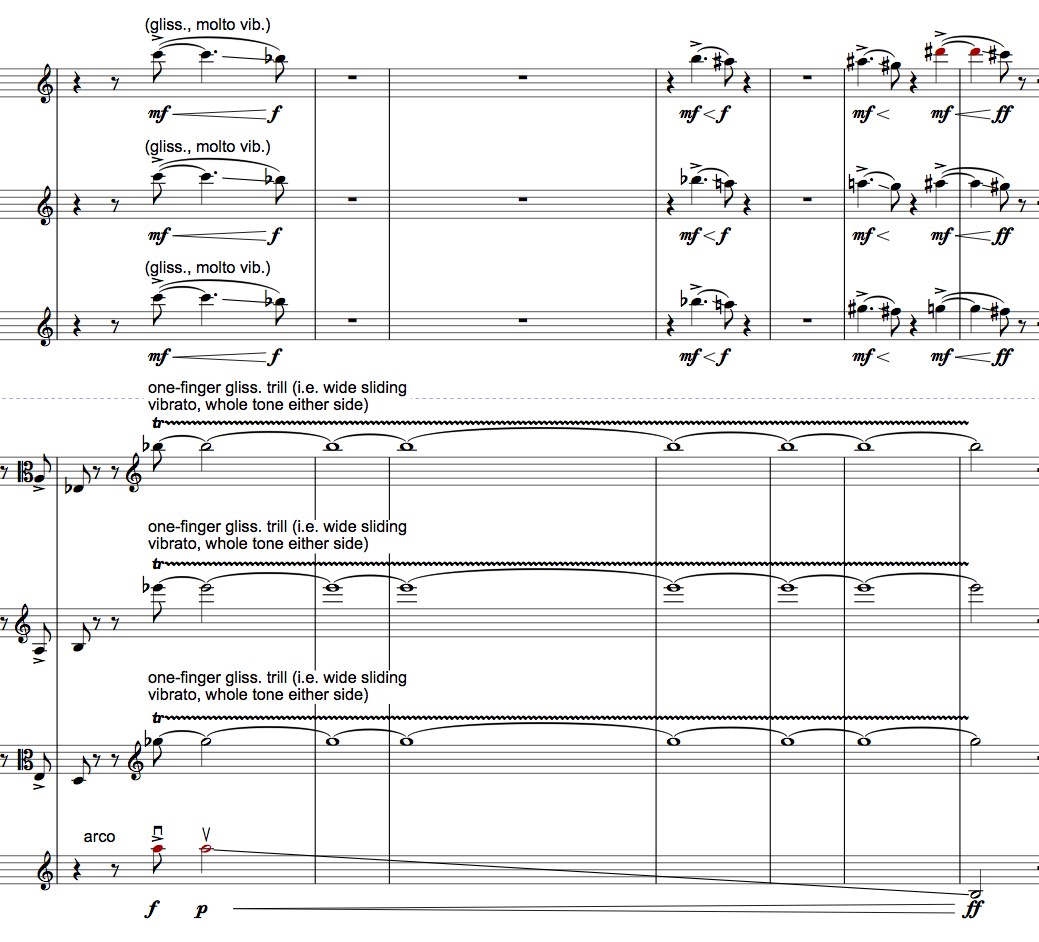

- The description of the patient “falling over, fainting and walking out in front of cars” is accompanied by wide, one-finger trills in upper strings, a long descending glissando in the bass and baritone saxophones playing short, downwards, glissandi gestures on high cluster chords, reminiscent of cartoon depictions of swerving cars, beeping horns, and the Doppler Effect as cars whizz by. See Scene 14, bars 99–105 and Figure 19.

Figure 19: An excerpt of the score for Scene 14 showing baritone saxophone and string accompaniment to the phrase “Patient kept falling over, fainting and walking out in front of cars”

In summary, Scene 14 was conceived as described, with projected text, downstage in blackout, text references supported by word painting in the music, without human voice heard or body seen, just like the Castellucci interlude. However, by the time of production it was clear that it was impossible to stage the scene this way, so the rehearsal process led to changes in approach.

Changing approach during rehearsals

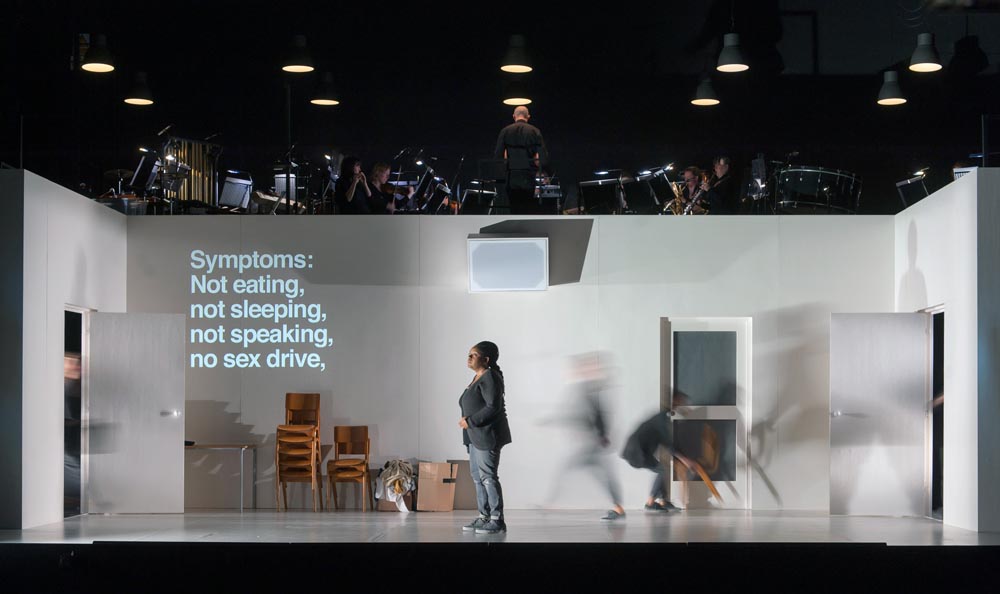

The staging concept of this production of 4.48 Psychosis involved the whole 6-member cast being on stage almost for the entire show, regardless of whether they were singing of not. In addition, there was no house curtain used nor scrim at the front of the stage; all projection was done onto the white walls of the set. Total blackout was also not possible because of stray light from the band music stands and the high visibility of the white walls. See Figure 20, a production photograph from Scene 14, which shows the set, a hive of fast activity around one static performer, Gwen, the projections on the upstage wall of the set, and the upstage position of the band above the set.

Figure 20: Photo of the opening of Scene 14 in this production of 4.48 Psychosis. Photo © Stephen Cummiskey

As the set was always visible and performers were always on stage, the Director felt it important to use this musical interlude to stage a fast, choreographed movement scene. We discussed approaches 2 and 3 above (see here), and agreed to try a recorded voiceover to better support the loud, lively music and the flurry of physical activity on stage, and to reinforce the use of voiceover, which was part of the style and language of the production. We tried both options: a male voice (approach 2), and a female voice from the cast (approach 3). During the rehearsal process we used MIDI mock-up tracks of the instrumental music with overdubbed voiceovers to test out both options.

The male voice was provided by Christian Burgess, Head of Drama at the Guildhall School of Music & Drama, a professional actor and director. His voice is particularly distinctive as ‘posh’, received pronunciation, rich and husky – suitable to represent the clichés of medical consultants. The female voice from the cast was Susanna Hurrell (Suzy) – also a clear voice with received pronunciation, and who provided the main voiceover for Scene 5B (see Chapter 7) that also describes the main character’s experiences with doctors.

In both cases, the voiceover was synchronised with the click track and the projected text, and both mock-ups were tried in staging rehearsals with the cast. Both voice recordings are available here:

Christian Burgess (male voice)

Susanna Hurrell (cast member, female voice)

A choice between the two had to be made. The male voice clearly signifies a voice that is other to the all-female cast, and therefore other to any physical representation of the patient on stage. However, as the only occurrence of the male identity in this production, this voice introduced gender problems. The male voice could suggest a patriarchal relationship between the patient and a/the doctor. It could also confuse the role of Lucy, who at several points in the production stepped out of the hive-mind cast to play the role of the doctor, either in a sung role in Scenes 2, 17 and 23, a voiceover role in Scene 18, or as a mime in Scenes 6, 10, 12 and 21. How would this distinctively male voice relate to the female doctor appearing in certain scenes on stage? There could be no ambiguity with a male voice; this voice could not be interpreted as part of a fantasy, a memory or a projection within the patient’s mind. It was too real.

The female voice from the cast allowed us to live within the hermetically-sealed hive-mind world we had created, without introducing a voice that was so clearly ‘other’. The ambiguity between real and fantasy, present and past, with which this production played in other scenes, would be maintained by using Suzy’s voice for the voiceover. The decision was made – approach 3 from the list.

The grammar of Kane’s text is clearly third person, but to support further the third-party point of view, the choreography of the scene did not single out a single body on stage to whom this voiceover could belong. It was very clearly outside of the stage action to the extent that the audience would not interpret this as ‘hearing inner thoughts’ in the way the Opera Thought-Bubble did in scenes 5A and 18. So, after trying three approaches and some experimentation during the rehearsal room, we settled on a solution that suited this production. Future productions may make different decisions, of course, such as reverting to the Castellucci-style text-only blackout scene. The score leaves these possibilities open, as discussed in Chapter 9.2.3 – Different directors.

Scene 14 from 4.48 Psychosis (28th May 2016): (video available on request)

5.2. Scene 16

The development of Scene 16 followed a similar path to the development of Scene 14, in the sense that they arrived at the same final treatment (voiceover with projected text) by the time of the premiere. However, Scene 16 was originally written as a rhythmically-complex chorus of live parlando voices with a soprano duet descant. No voiceover was conceived, but a live sung-spoken performance. I will discuss how this change towards voiceover and projection happened as a solution to practical problems exposed by workshops.

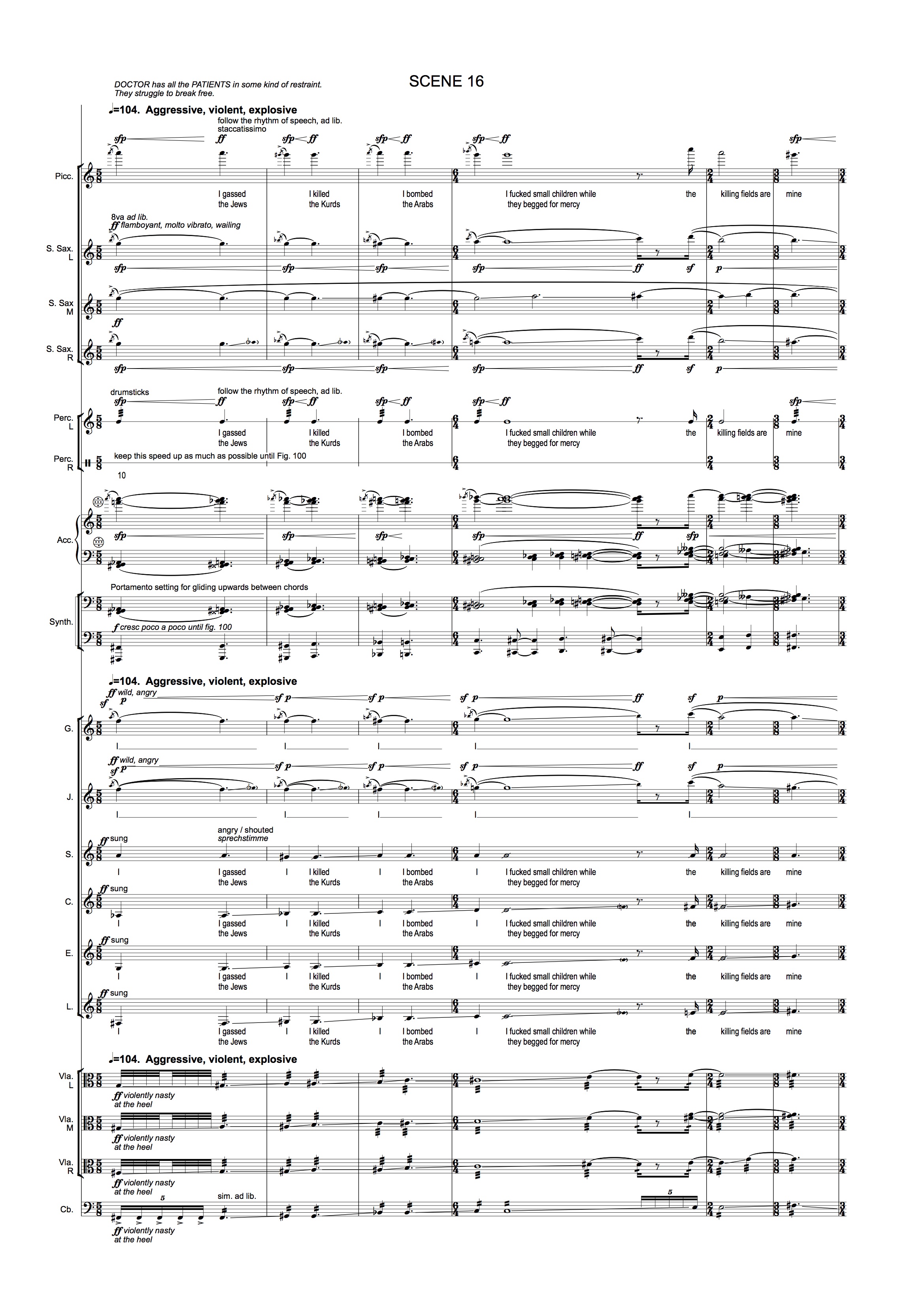

The first part of Kane’s text for Scene 16 is given here (Kane 2000: 25), clearly indicating the prevailing anger of the scene through historical references, descriptions of violence, swearing, use of capitals:

– I gassed the Jews, I killed the Kurds, I bombed the Arabs, I fucked small children while they begged for mercy, the killing fields are mine, everyone left the party because of me, I’ll suck your fucking eyes out sent them to your mother in a box and when I die I’m going to be reincarnated as your child only fifty times worse and as mad as all fuck I’m going to make your life a living fucking hell I REFUSE I REFUSE I REFUSE LOOK AWAY FROM ME.

An example of the original scoring of Scene 16 is shown in Figure 21. The pattern of this vocal writing for the lower four voices follows the same pattern as in Scene 3: the ‘I’ of each phrase is sung in metre and the remaining text is spoken in free rhythm (see also the discussion in Chapter 6.1– Scene 3). Figure 21 shows that the piccolo and snare drum players were also required to articulate these free speech rhythms, in approximate synchronisation with the four voices.

Figure 21: First page of the original version of Scene 16, showing a sung chorus with descant and text-rhythms for snare drum and piccolo.

This version of Scene 16 was rehearsed with singers and ensemble in the Year 3 Read-through workshops in January 2016. The full score for this version and a recording of this workshop run-through is available here: Scene 16 first version. The recording is here:

The workshops made clear:

- the ensemble and two descant sopranos overpowered the spoken chorus

- the vocal lines lacked the biting anger of Kane’s text, because the voices sounded too controlled, and the singers were avoiding proper shouting.

- the harmony and orchestration in the ensemble was mis-judged and sounded too derivative of bombastic, superficial drama.

- A rehearsal process would necessitate rhythms for spoken text being decided and learnt, negating the freedom in the original writing.

- Singing this scene was exhausting for the cast. If a non-live version of this scene were made, it would give the singers a valuable rest during an opera that already required great stamina.

Given these problems, the director, conductor and I agreed that this scene would be best without live voice but with projection only. This decision thereby changed the relationship between performer, text and voice: rather than expressing the anger of this scene through live vocal performance, anger would remain in the projected words only, and could be supported physically through staging. In the new version, the ensemble music would stay roughly the same, with some corrections to harmony and orchestration, and the rhythms for piccolo and snare drum would be written out to address the problems described above.

This projection-only version was tested in rehearsals, but was found to be not fully effective in fully delivering the anger of the scene against the loud music and the stage action. The unbridled shouting / screaming that is suggested by Kane’s use of capitals was lacking, and the Director and I felt that the scene could benefit from a voiceover recording of the text.

We could not ask singers to scream and shout, so Sarah Fahie, our movement director, offered to give an impassioned performance of the text at full volume screaming. This was recorded in the studio and played as a voiceover with the music and projection. Unlike the original version of this score, which synchronised the live shouted/sung text and the music, this pre-recorded voiceover was not synchronised. The projections were cued manually by the DSM in sync with the pre-recorded voice rather than the music, so the link between text rhythm and musical rhythm was lost. (Automation of this cueing could be done, since the timing of the voiceover recording is fixed. We may do this in the 2018 revival.) The projections appeared more like surtitles to a pre-recorded shouted text. You can hear the audio of the voiceover here:

The unsynchronisation led to the interesting ramification that the voiceover finished about six seconds after the music, when played at the indicated tempo. The words I REFUSE I REFUSE LOOK AWAY FROM ME overspilled and were accompanied only by the fading air-raid siren that continues after the ensemble has stopped playing (see Scene 16, Figure 16C). This ‘untidiness’ seemed appropriate to combat the problem of music and voice sounding too controlled, too ‘composed’, in this scene.

The overall result was a text-voice-projection relationship similar to that of Scene 14, except that in Scene 16 the synchronised projection and voice were not synchronised with the music. However, the routes to these two solutions were very different, but both involved trial and error experimentation. In the case of Scene 16, practical issues came into play, and the voiceover was added because it enabled us to achieve a vocal quality that would not be possible with a trained singer, neither live nor pre-recorded. The finalised score, however, retains the synchronised projection cues and only a performance note that a voiceover may be included, at the discretion of the director. Further discussion of such issues are discussed in Chapter 9 – Evaluation.

Scene 16 from 4.48 Psychosis (28th May 2016): (video available on request)

5.3. Scene 11

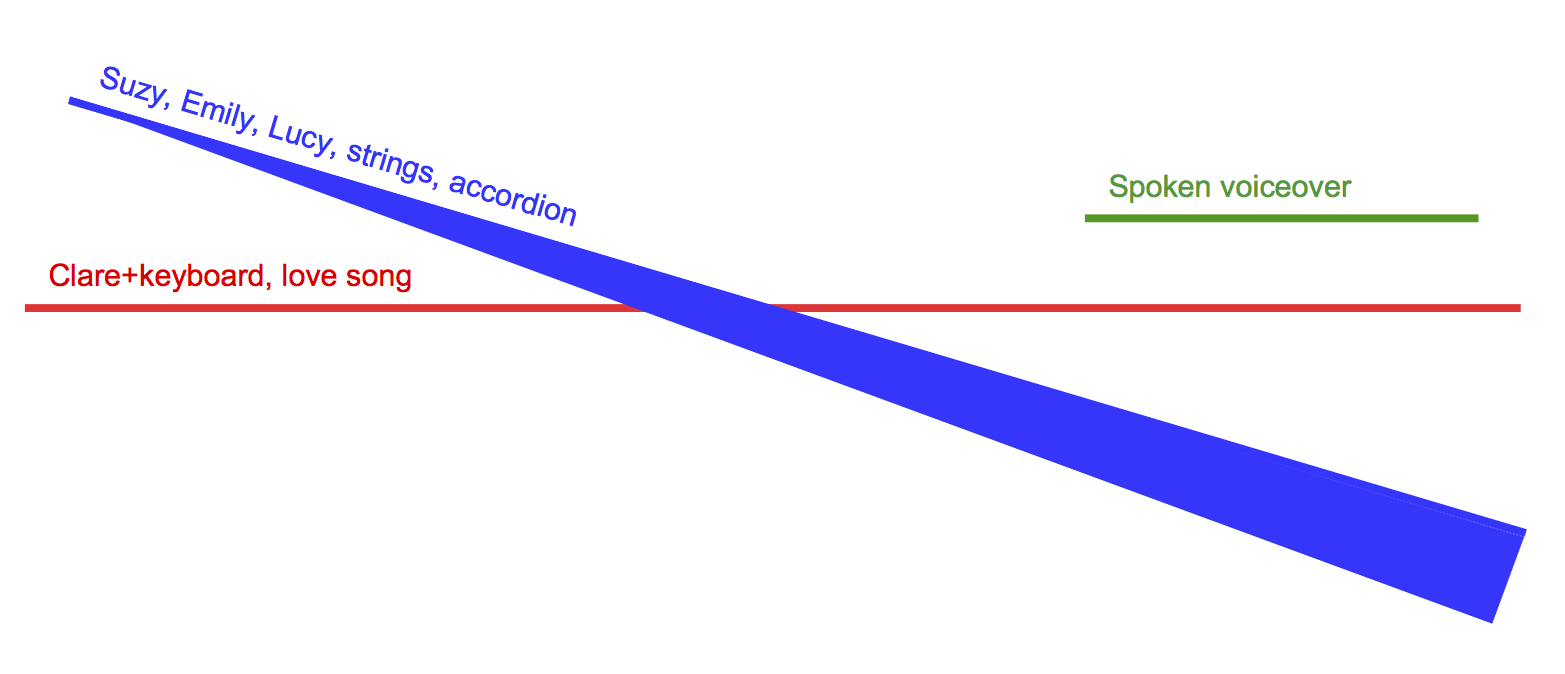

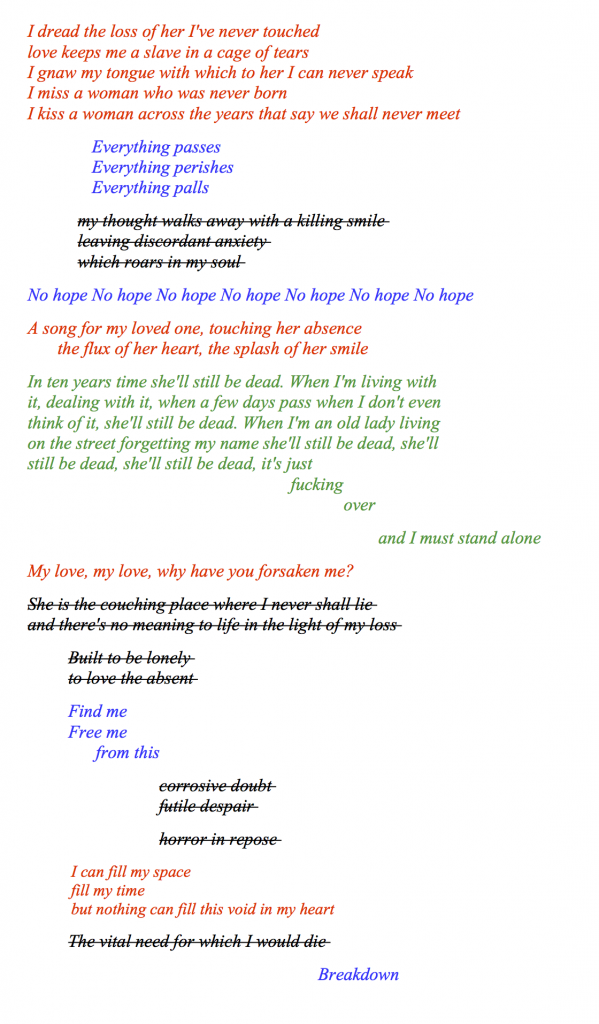

Scene 11 shows an example of voiceover without projected text. The scene setting is constructed of three independent strands, shown in Figure 22. Kane’s text in this scene was divided into three groups accordingly, colour-coded as shown in Figure 23, and showing cut text. Gwen and Jen do not sing, and the strands are dramaturgically, musically and temporally independent.

- Red: The primary strand features a stand-alone love song for Clare accompanying herself on a small keyboard, reminiscent of a familiar scene – the teenager sitting alone in their bedroom indulging adolescent depression by playing / singing pop songs*.

- Blue: Emily, Lucy, Suzy singing short repeated phrases.

- Green: Spoken voiceover In ten years time.

(*That was the dramaturgical conceit for this scene, although in the production the keyboard part was recorded rather than played live. The director, conductor and I have agreed to try to reinstate the live keyboard part in the scheduled revival in 2018.)

Figure 22: Diagram showing the three independent strands of Scene 11, with relative pitch and volume

Figure 23: Kane’s text for Scene 11, showing attribution of lines to three independent musical strands, and cuts.

The point of view of the green voiceover text is ambiguous. It is unclear whether ‘she’ refers to the main character in the third person, or to an imaginary lover. In other words, whether this voice is that of the main character or the voice of a third party, a lover. To play with that ambiguity, we decided to remove this text from the live stage action and instead place it in voiceover, but to record the text with Gwen’s voice, who is most established throughout the opera as the lead proponent of the main character ‘hive-mind’ and whose spoken voice we have heard most of through the opera. Therefore the voice could be ambiguously heard as external/third-party (because it is outside of the stage action) or as the main character (because it is Gwen’s voice). As Gwen does not sing in this scene at all (although in this production she was on stage and involved in physical action in this scene), her voice is not associated with a singing action, and therefore is not to be read as an inner monologue of a singing character on stage. In other productions she could be absent from the stage altogether.

In this chapter I have discussed voiceover techniques distinct from the thought-bubble technique described in the previous chapter. Scene 11 uses a more traditional voiceover, unsynchronised to any musical metre, live sung gestures, nor projected text. In contrast, Scenes 14 and 16, after a period of workshops and rehearsal changes, arrived at a similar construction of a voiceover synchronised with projected text and, in the case of Scene 14, also with music. Having dealt with two dramaturgically different kinds of voiceover in these two chapters, I will now move on to spoken text delivered in live performance.